“Esto fue una sorpresa para nosotros”, dijeron los autores. “Se dice que la fuente de nuestro material genético es considerablemente más amplio de lo que pensábamos. Incluye nuestros propios genes y los inesperados genes virales también.”

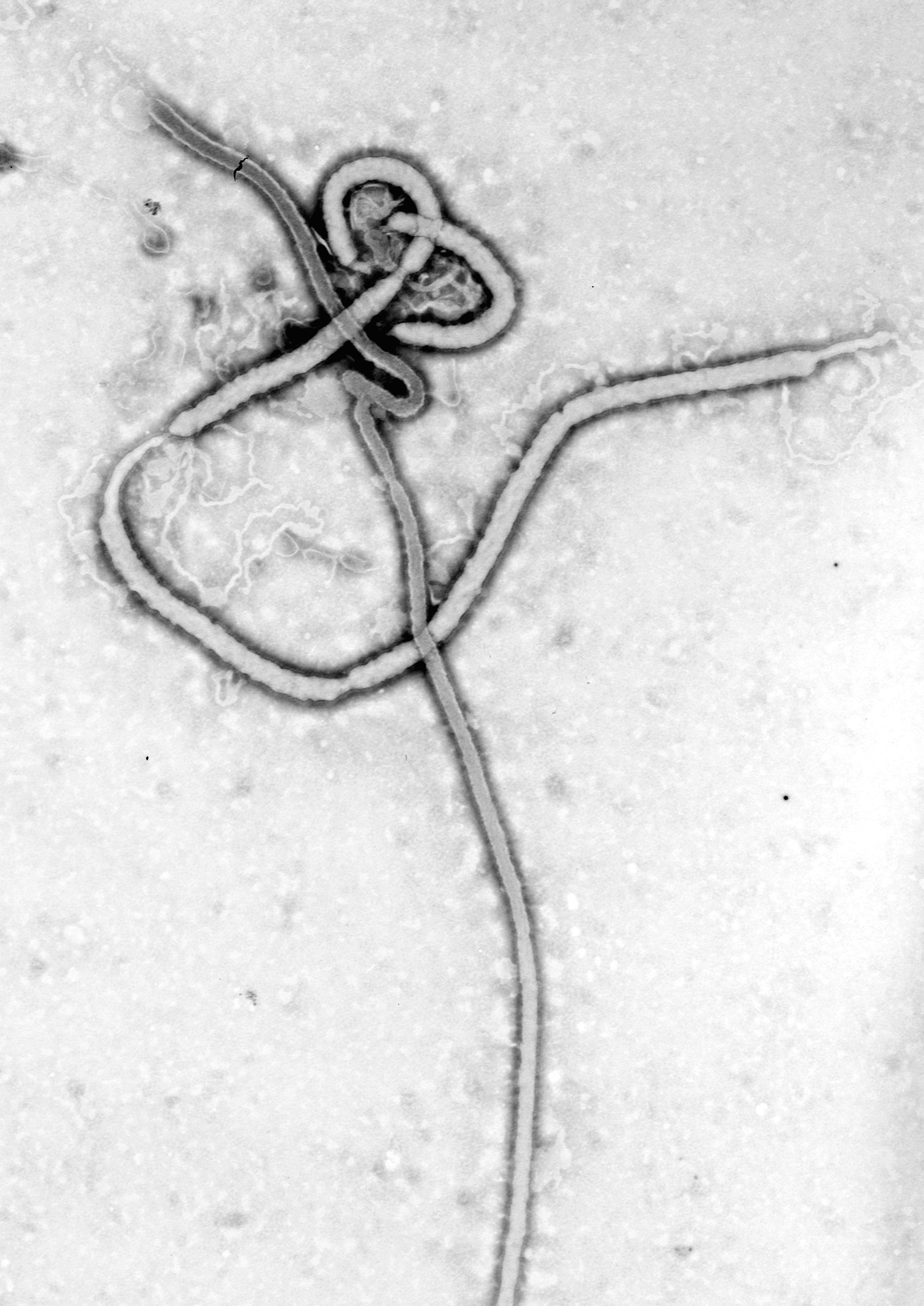

El equipo del Instituto de Estudios Avanzados de Princeton, comparó con 5.666 genes de todos los virus conocidos no retrovirales (genomas de ARN) con los genomas de 48 especies de vertebrados, incluyendo los humanos. Al hacerlo, descubrieron 80 integraciones separadas de secuencias virales en 19 diferentes especies de vertebrados. Curiosamente, casi todas las secuencias virales provienen de antiguos parientes de dos únicas familias virales, la fiebre hemorrágica de Ébola/Marburgviruses y la Bornaviruses, los cuales causan fiebres hemorrágicas y las enfermedades neurológicas.

“Estos virus son virus de AR, ellos replican su ARN y se sabe que no hacen ninguna copia de ADN. Y no tienen ningún mecanismo conocido para obtener su material genético integrado en el ADN del genoma del huésped. De hecho, algunos de ellos ni siquiera entran en el núcleo cuando se replican. ” De ahí lo sorprendente del hallazgo.

Francisco P. Chávez Ph.D

Departamento de Biología, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad de Chile.

http://www.bioblogia.com

Imagen: Wikipedia

Unexpected Inheritance: Multiple Integrations of Ancient Bornavirus and Ebolavirus/Marburgvirus Sequences in Vertebrate Genomes.

Belyi VA, Levine AJ, Skalka AM. PLoS Pathogens, 2010; 6 (7): e1001030 DOI:10.1371/journal.ppat.1001030

Abstract

Vertebrate genomes contain numerous copies of retroviral sequences, acquired over the course of evolution. Until recently they were thought to be the only type of RNA viruses to be so represented, because integration of a DNA copy of their genome is required for their replication. In this study, an extensive sequence comparison was conducted in which 5,666 viral genes from all known non-retroviral families with single-stranded RNA genomes were matched against the germline genomes of 48 vertebrate species, to determine if such viruses could also contribute to the vertebrate genetic heritage. In 19 of the tested vertebrate species, we discovered as many as 80 high-confidence examples of genomic DNA sequences that appear to be derived, as long ago as 40 million years, from ancestral members of 4 currently circulating virus families with single strand RNA genomes. Surprisingly, almost all of the sequences are related to only two families in the Order Mononegavirales: the Bornaviruses and the Filoviruses, which cause lethal neurological disease and hemorrhagic fevers, respectively. Based on signature landmarks some, and perhaps all, of the endogenous virus-like DNA sequences appear to be LINE element-facilitated integrations derived from viral mRNAs. The integrations represent genes that encode viral nucleocapsid, RNA-dependent-RNA-polymerase, matrix and, possibly, glycoproteins. Integrations are generally limited to one or very few copies of a related viral gene per species, suggesting that once the initial germline integration was obtained (or selected), later integrations failed or provided little advantage to the host. The conservation of relatively long open reading frames for several of the endogenous sequences, the virus-like protein regions represented, and a potential correlation between their presence and a species' resistance to the diseases caused by these pathogens, are consistent with the notion that their products provide some important biological advantage to the species. In addition, the viruses could also benefit, as some resistant species (e.g. bats) may serve as natural reservoirs for their persistence and transmission. Given the stringent limitations imposed in this informatics search, the examples described here should be considered a low estimate of the number of such integration events that have persisted over evolutionary time scales. Clearly, the sources of genetic information in vertebrate genomes are much more diverse than previously suspected.